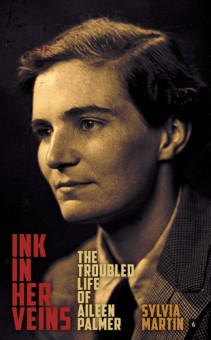

Ink in Her Veins is the newly published biography of Aileen Palmer (1915-1988) – daughter of Nettie and Vance – by Sylvia Martin who, it seems to me, is well on her way to joining the first rank of Australian literary biographers. This is Dr Martin’s third biography, after Passionate Friends (2001) on poet Mary Fullerton and her friends, Mabel Singleton and Miles Franklin (my review here,) and the Margarey Medal-winning Ida Leeson: A Life– Not a bluestocking lady (2006).

One of the attractions of Ink in Her Veins is the new view it provides into the lives of Nettie and Vance Palmer, and their wide circle of literary friends and correspondents. Martin’s research is necessarily based on this correspondence, but there are also letters between the Palmers and their two daughters (Aileen’s sister Helen was born in 1917), many failed/unpublished attempts by Aileen to fictionalise her life, and interestingly, snippets of gossip from Henry Handel Richardson and Frank Dalby Davidson writing to others. In consequence Martin has been able to produce a detailed and fascinating account.

Nettie’s family was pretty well off, her father, John Higgins, was an accountant. His sisters had both attended university and his brother, Nettie’s illustrious uncle, High Court Judge Henry Bourne Higgins, made sure Nettie did too (my post on the education of Nettie’s generation here). Nettie rejected her parent’s Baptist religion but there is no doubt her strict upbringing was an influence throughout her life. Nettie was forced to endure a long engagement to Vance while he got his career as a journalist and writer underway and, importantly for our understanding of Aileen’s later life, while he dealt with the committing and institutionalisation of his brother. Finally, in May 1914 when they were both 29, the stars aligned and Nettie having joined Vance in London (from Melbourne), they were married in a Baptist chapel the following day.

For the first of many times throughout their married life, Nettie and Vance took a cottage in a seaside village where they could work and relax, in this case Tregastel in France. Of course, within two months war had broken out and the Palmers, with Nettie already pregnant, returned to London. Vance went on, briefly, to New York to secure new writing jobs, while Katherine Sussanah Prichard who was to be an important friend to Aileen, moved in with Nettie. Shortly after Aileen was born, the Palmers returned to Melbourne, and thence to another seaside village, Caloundra in Queensland, where they purchased some land with some money from Nettie’s father.

Martin suggests that “Nettie’s fierce and almost excessive support of Vance’s career may have been pursued, at least in part, to compensate for the continuing necessity of her parents’ assistance, which she knew would be bruising to her husband’s ego.” Later, Aileen was to blame the truncation of her mother’s career as a poet not just on her support for Vance, but as well on herself, on the demands she and Helen made on Nettie as their mother.

Aileen’s life may be considered in 3 parts – her schooling, initially in Caloundra then, from 1929, back in Melbourne at PLC and Melbourne Uni; the years of the Spanish Civil War and World War II; and the rest of her life, mostly back in Melbourne, dependent on her parents, struggling with mental illness. Throughout, we see her parent’s socialist politics manifest in her (and Helen) as a firm commitment to Communism; a preference for same-sex relationships which she seems mostly to repress, and certainly to conceal from her parents; and a conflicted relationship with her parents, particularly with Nettie, where she strives to achieve their ambitions for her, is dependent on them for money, and even at a young age is over-involved with their work, typing and proof-reading for Vance and acting as secretary for Nettie.

Aileen did well at PLC, had the usual crushes on attractive teachers, and did a lot of writing. ‘Poor Child!’, an early unpublished novel – it seems all her novels were autobiographical – suggests she was already suffering depression. At uni where she studied French and German, she became politically active through the Labour Club, which when I joined it in the late 60s was Fabian socialist (and they soon suggested I would be better off with the Anarchists), but which back then in the 1930s was firmly communist. She was also “received into the ranks of a small and select group of female Arts students who referred to themselves as the Mob. Older than Aileen, her new friends set about initiating her into Mob philosophy of spontaneity, free love and worship of trees.”

Martin muses on the problem of the biographer with too many sources:

Sometimes I have felt that working on Aileen Palmer’s autobiographical writing, in which actual people and places are given fictional names (and not always the same ones), is a little like entering a hall of mirrors where nothing is quite what it seems. [A] fictionalised memoir based on the real letters and diaries of the group … helps to illuminate the arcane and mysterious world of Aileen’s diary at the same time as it adds another cryptic layer. But Aileen’s diary itself further confuses the boundaries between fact and fiction by including some of the fictional characters from ‘Poor Child!’ in it.

In the final year of university, Aileen’s active involvement in left wing politics saw her heavily involved in the protests around the Lyons government’s notorious attempts to deport the Czech, communist (and multi-lingual) writer Egon Kisch who had been invited to address the Movement Against War and Fascism. Intellectuals active in the nation-wide protests included the Palmers, KSP, and Louis and Hilda Esson. The following year, 1935, Vance and Nettie took the two girls to Europe. According to Aileen, “[Nettie] said to someone, ‘We want the children to see something of Europe before it is blown up’. Which seems a frivolous way of putting it now, since I’ve seen a bit of what blowing up can be like …”

The Palmers went first (of course) to London where Aileen became increasingly involved with the local Communists, attending conferences with Helen, going to rallies and selling the Daily Worker on street corners. Her parents farmed her out to a secretarial job in Vienna for a while, then in 1936 Helen returned to Australia to commence university, Vance was commissioned to undertake the abridgement of Furphy’s Such is Life (subject of an earlier post here) and Nettie, Vance and Aileen set out to spend the year in another seaside village, this time Montgat in Catalonia (on the Mediterranean, north of Barcelona). Aileen was soon involved with the anti-Fascist movement in Barcelona, but when Franco rises up against the elected government, Aileen and Vance take fright and remove her, and themselves, to London. Within a month Aileen is back, a translator-secretary with the first British Medical Unit into Spain (subsequently folded into the International Brigades), while her parents return to Australia, where it must be said, they were active in supporting the Republican side.

Aileen spent two years all up in Spain, nominally in admin but often up to her elbows in blood, working in tents and huts as a field hospital orderly. As the Francoists prevailed and the IBs were withdrawn, she returned to London, but in another year Hitler had set off WW II and Aileen was once again doing war work, with a unit of the Auxiliary Ambulance Service, rescuing victims from bomb sites in the Blitz. In a story called Ambulance Station she writes:

‘There’s something over there on the pavement’, I tell one of the stretcher-party men, ‘that was once somebody’.

The body is lifted up and placed on a stretcher, beside another dead woman.

No time for any more words. More ambulances are coming to carry off similar grim loads. Everyone speaks with a harsh, dry utterance that expresses a kind of inner numbness. So much piled-up death, so much plain butchery – it is too horrible to be pathetic.

For a while Aileen lives with another woman, ‘B’, who she does not name in any of her writings, and is happy in love. As the war grinds on she eventually gets out of ambulance work, and finds a less distressing job at Australia House. She probably also has one other love affair. Not yet aged 30, it’s her last.

After the war she returns to Melbourne to live in the family home, Ardmore in Kew. Probably, she is bi-polar – she writes of being happy mad and depressed mad – anyway, her mother, who has always been controlling and her sister, who is ‘practical’, get her committed and so she commences years in and out of residential care, and constant shock treatment.

In the end, the woman who felt she should be a novelist like her father, had just one or two slim volumes of poetry published. Martin appears to feel very strongly that it was Nettie who failed Aileen. She quotes a letter by Aileen to KSP:

I feel very grateful when anyone reminds Nettie that my own writing is one of those things that matters. She’ll never be very interested in it, I feel, but it still strikes me as extraordinary at times, after the way she impressed on me profoundly as a young child that writing was the thing above all others worth spending one’s life on, and how she treasured and carted from pillar to post the exercise books I filled with novels from the age of nine or ten, how little interested she is in what I have to say as an adult.

Finally, if there is one shortcoming it is the absence of footnotes. Ink in Her Veins uses the system I complained about in my review of M. van Velzen’s Call of the Outback: at the back of the book “a long list of page no.s and phrases with their sources, which might have been informative if only we could have referred to them while following the text”. A system it seems I’ll just have to get used to, but, thankfully, there is at least this time a comprehensive index.

Sylvia Martin, Ink in Her Veins: The Troubled Life of Aileen Palmer, UWAP, Perth, 2016

Reviews:

Nathan Hobby at A Biographer in Perth or at Westerly

Drusilla Modjeska in the SMH/Age.

Sylvia Martin, The Lost Thesis (here)

Sylvia Martin , The Lost Portrait (here)

Fascinating! This one is on my radar, as indeed is anything about the Palmers. There’s a book about Australian literature by Nettie which I’d love to track down…

LikeLike

You can see by all the links I had to put in how closely this biography links in with the pre-WW II literary scene, but the best part is probably the war in Spain, which I barely covered.

LikeLike

I love that biographers are working on these writers from the past – and their families. I’ve read a little about the Palmers and poor Aileen, so would love to read this.

I agree with you and have commented too, on the issue of footnotes and endnotes. I don’t mind if they are endnotes, but, as you say, I’d like to know they exist as I’m reading rather than having to keep looking at the back just in case. I think this – and indexes – are the two things that are given short shrift in books aimed primarily at a general market, rather than an academic one, and it’s a shame.

LikeLike

I’m afraid you’ll have to do as Lisa does – and I do too – and forget what I have written so you can read it for yourself. Ink in her Veins, is both well written (and documented) and very informative about one Australian’s involvement in the Spanish Civil War.

LikeLike

Ha ha, Bill , maybe! I do tend to read nonfiction blog reviews. It’s not about spoilers but impressions and meanings. I want to come at them as freshly as possible. That doesn’t seem to worry me so much with non-fiction

LikeLike

Dr Martin writes: The format for notes is a really difficult decision to make, but I decided not to put endnote numbers in the text as some readers find them distracting and off-putting and I wanted the book to appeal to readers who want to simply follow the narrative…

Also, I’ve added a link to Drusilla Modjeska’s review in the SMH/Age.

LikeLike

Hmmm … one is inclined to think lowest common denominator but I suppose that’s unkind. The info is there, I guess, just harder to locate.

LikeLike

UQP published a sort of compendium of her works some time ago, Lisa, just called Nettie Palmer (edited by Vivian Smith). Look out for it in second hand bookshops. It contains her journals, poems, reviews and literary essays. It includes her survey Modern Australian Literature, 1900-1923. I have an electronic version on my iPad but so far have only read the introduction, which is very good, and other little pieces.

LikeLike

I have that one, 550 pp though I’m not sure how much of it I’ve read, but certainly all her journal. Published 1988.

LikeLike

that’s it, and yes, 550 or so pages.

LikeLike

AH, that explains why my searches have been fruitless… thankyou!

LikeLiked by 1 person

In my rush last night I forgot to say Nathan is also doing a review, to appear in Westerly but also I’m sure, in A Biographer In Perth. I’ll put up a link when it comes out.

LikeLike

Thanks for the wonderful review Bill. I also enjoyed this biography a lot. It is a gripping narrative, something too few biographers aspire to or achieve.

I wondered about how much Aileen’s problems were Nettie’s fault – the biography reveals some mistakes, but she also seems to have been a loving mother. It was not a good age to be a lesbian or someone suffering mental illness.

I wrote a review, but I’m not sure when it will appear on the Westerly blog. I picked that same quote about the ‘hall of mirrors’ and some similar sentiments on referencing.

LikeLike

Gripping is a great description. I think you would enjoy reading Ink in her Veins even if you didn’t know (of) the Palmers.

As for Nettie to blame, I think Martin blames Nettie perhaps more than I would. I loathe the whole idea of shock treatment (psych daughter told me off about this and made me read an essay about it) but it was probably a valid treatment at the time. N and V never really seem to ‘let go’ of their daughters.

LikeLike

[…] Bill also reviewed this book last month – https://theaustralianlegend.wordpress.com/2016/04/22/ink-in-her-veins-sylvia-martin/ […]

LikeLike

[…] out and came home to enlist in the AIF. We know from Sylvia Martin’s biography of Aileen Palmer (my review) that Vance was actually on honeymoon with his new wife Nettie in France when the Great War […]

LikeLike

[…] Free Square: Saving the best for last? Well maybe. I’ve read some excellent books by (and about) Australian Women Writers this year and this is definitely one of them. Sylivia Martin’s life of poet, activist (and daughter of Nettie and Vance) Aileen Palmer, Ink in her Veins (2016) – Review […]

LikeLike

[…] but probably the best I read was Sylvia Martin’s biography of Aileen Palmer, Ink in Her Veins (review). Even amongst all your reviews I did not see any fiction to rival Patric’s Black Rock White City […]

LikeLike