In April 1889 Ethel Richardson, who was then 19, and her sister Lillian, a year younger, enrolled at the Royal Conservatorium in Leipzig, Germany to study respectively piano and violin. Over the next quarter of a century, till WWI, both young women were immersed in German culture. By 1895 Ethel had graduated with honours and was married to John Robertson who was to become the preeminent English scholar of German literature; and Lillian was married to Otto Neustatter, a German eye-specialist.

During the same period, Cosima Wagner, the widow of composer Richard Wagner, was the director, from 1885 to 1907, of the famous Bayreuth Festival established by the Wagners in 1876 as a setting for performances of the Ring Cycle.

Cosima (1837-1930) was the second (illegitimate) daughter of Franz Liszt and Paris socialite Marie d’Agoult. Cosima and her sister were strictly schooled, in Paris, but by 1855 Liszt had taken up with Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein and wanted the girls out of their mother’s orbit. He sent them to Berlin, at that time a provincial capital, to the care of the mother of his former star pupil Hans von Bülow (1830-1894). By 1857 Hans and Cosima were married.

Ethel of course is the PLC, Melbourne-educated Australian author Henry Handel Richardson, and this, her last novel, is a fictionalised account of the story, which one can imagine was told in hushed tones to newcomers like the Richardson sisters, of Cosima’s cuckolding of von Bülow, and eventual marriage to the much older Wagner. (HHR may have written another ‘last’ novel, about the dissolution of her sister and Neustatter’s marriage when they were separated during the War, but the ms was lost, possibly burnt.)

In her Henry Handel Richardson: A Study (1950) Nettie Palmer writes:

There is strong emphasis on the name of the novel. For its duration Cosima remains young. But it is an emphasis of contrast. Most readers, as well as the author, are keenly aware of that other figure of Cosima, growing old, very old …

In fact in 1939 when the novel came out, Cosima Wagner had died just 9 years previously, aged 93, and although she had long ago relinquished day to day control of the Bayreuth Festival, she had been a force in European culture for most of her adult life.

HHR takes up the story in 1855. Cosima and her older sister Blandine are in Berlin with Frau von Bülow, Liszt and Princess Carolyne are in Weimar, and Wagner and his wife Minna are in exile from Bavaria, in Switzerland. Von Bülow who has a low paying position at the Stern Konservatorium, is attempting to make a career as a conductor/performer/advocate for the ‘futuristic’ music of Liszt and Wagner.

Throughout, HHR calls Cosima “Cosette” and ascribes to all the principal characters detailed speech and thoughts. It is difficult to know what if any access she had to the correspondence of Wagner and Liszt, who died respectively, in 1883 and 1886, but on the other hand, as a university wife HHR would have known people who knew Cosima personally and probably people a generation or so older who knew Wagner, Liszt and von Bülow.

The detailed speech is a problem, it appears clumsy, especially early on, and while that of course may be me misunderstanding HHR’s rendition of formal German and French, it is also an explanation of why this is her least appreciated novel. Here, Liszt has been waiting to breakfast with Carolyne, his partner of seven years:

Liszt took possession of the dimpled hands, and, having kissed each in turn, laid them together and kissed the two as one. After which he said, in French: “My adored one, good morning! How have you rested?”

“Well my friend. And you? I trust I have not kept you waiting. The fact is I disposed of some trivial correspondence before rising.”

“No matter! Where you are concerned even to wait is a pleasure: for can I not anticipate your coming? It is only that the day is dark for me till you appear. But now you are here; and the sun, my sun, shines again.”

At this, a bare, massively-rounded arm emerged from its loose sleeve and was laid with consoling pressure on his; as though to say, I know, I know.

Palmer asks, “How far is an author justified in assuming omniscience like this about characters with a place in history?” Interestingly, she doesn’t answer directly, but I think suggests that one justification for historical fiction is to interrogate the motives of a central player, in this case, Cosima. After a hesitant beginning in which the author is constrained to present a mass of historical detail: “It is only when she begins to penetrate the inner being of Cosima that the book takes on the character of a created work … above and apart from the biographical fragments of which it is so faithfully made.”

Further, Palmer writes that unlike in Maurice Guest where the music is only incidental to the tensions between Guest, Louise and Schilsky:

In The Young Cosima… the atmosphere of music in which the chief characters are steeped determines all their relationships…

In what milieu other than the heady one evoked by the creation of great masterpieces could Cosima, a spirited young woman in her middle twenties, forsake home, husband and the religious faith to which she was attached for a man old enough to be her father? The relations between the men themselves – Wagner, Liszt, Hans von Bülow – are no less complicated than those between them, severally, and Cosima.

In brief, the story of The Young Cosima is as follows. Cosima, herself a gifted pianist, overcomes the opposition of the Princess and von Bülow’s mother to marry von Bülow and determines to be his helpmeet in every way, first in the house, and then in the advancement of his career, particulary his composing. She prepares storylines for Oresteia and then for Merlin – A Music Drama. “In short, she began to have ideas of her own for the construction of a symphony, without, alas! the manly ability to supply a note of the music.” But both efforts are wasted.

Von Bülow is violently argumentative in pursuance of his unpopular cause, which means he is often derided in the Berlin press, and works very long hours at unpaid work for Wagner, particularly the transcription to piano of Tristan and Isolde, and rushes to his side at every opportunity. On one visit to Zurich, von Bülow and Cosima become embroiled in the violent arguments of Wagner and Minna, over Wagner’s dalliance with his current patroness, that eventually lead to the Wagner’s separation.

Slowly, but brilliantly, HHR builds our understanding of Cosima as she grows into adulthood, and then motherhood, but is increasingly held at arms length by von Bülow as his career begins to take off. Slowly too Cosima warms to Wagner, forgiving his impossible demands on her husband, tentatively at first, accepting his friendship, sleeping with him, then over the summer of 1865 as the tension builds for the first ever performance of Tristan and Isolde before Wagner’s new patron, the young King Ludwig of Bavaria, taking over all his paperwork, it becoming understood “that the Master himself would look with favour on civilities shown the lady who acted as his secretary.”

Still, Cosima returns to Berlin with her husband and children, but von Bülow discovers a private letter between the lovers and the negotiations begin. For months, as in the background Prussia wages war to unite Germany, von Bülow is forced to maintain the appearance of marriage while working with Wagner to bring about the completion and performance of the Meistersinger. Then and only then do Cosima and Wagner make it clear to von Bülow that the only way forward is divorce.

The Young Cosima starts slowly, but builds and builds to an emotional climax. Read it.

Henry Handel Richardson, The Young Cosima, First pub. 1939. This ed. Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1984 ((c) Olga Roncoroni 1976 so it may have been re-edited for A&R)

Nettie Palmer, Henry Handel Richardson: A Study, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1950. Kindly lent to me by Lisa Hill of ANZ LitLovers (her review here).

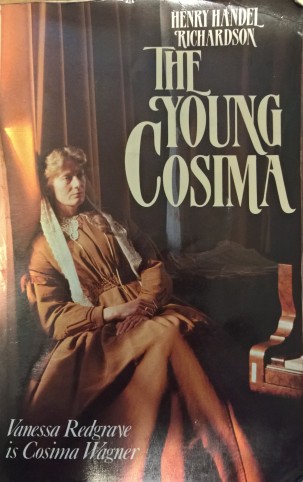

The cover photo is of Vanessa Redgrave as Cosima in the 1983 movie Wagner, starring Richard Burton and directed by Tony Palmer. In its uncut form it is 7 hours 46 min long!

The Wikipedia entry for Cosima Wagner (here) is detailed and well written and of course has links to Liszt, von Bülow and Wagner.

Richard Wagner, and apparently Cosima too, were notorious anti-semites. This is not remarked on by Nettie Palmer, though in 1950 perhaps she might have. HHR has Wagner referring to Jewish money lenders a number of times, for instance on p.183 “I’ve tapped every Jew-man I’ve ever heard of” and once in an anti-Germany rant (which Palmer also quotes) to the “Jew-ridden press”.

This is the one I haven’t read, but it sounds most interesting (as long as there’s not too much of that stilted translation!)

The anti-Semitism sounds unpleasant. I hope she regretted it.

LikeLike

The dialogue gets better! And there’s a great sense of involvement as Wagner churns out these masterpieces, which I didn’t really convey in my review.

I couldn’t ignore Wagner’s anti-semitism, hence my para at the end and I’m disappointed that Nettie could. My impression, guess really, is that HHR attempted to down-play it.

LikeLike

[…] among my own posts for the year is The Young Cosima, Henry Handel Richardson, 11 Nov 2016 (here), partly because of the considerable research it required for me put the story into its correct […]

LikeLike

[…] Henry Handel Richardson, The Young Cosima (review). Some people may attach some importance to Patrick White’s first, Happy […]

LikeLike

[…] will treat at length ‘one day’ soon; and Ethel (Henry Handel) Richardson (1870-1946) here and […]

LikeLike

[…] George is friends with Franz Liszt and stays with him in Switzerland in time to meet baby Cosima (The Young Cosima, Henry Handel Richardson). Liszt introduces her to Frederic Chopin, and Sand and Chopin live together for the decade […]

LikeLike

[…] George is friends with Franz Liszt and stays with him in Switzerland in time to meet baby Cosima (The Young Cosima, Henry Handel Richardson). Liszt introduces her to Frederic Chopin, and Sand and Chopin live together for the decade […]

LikeLike

[…] Henry Handel Richardson, The Young Cosima, 1939 (review) […]

LikeLike

[…] Maurice Guest (1908)(Lisa’s ANZLitLovers review) and The young Cosima (1939) (Bill’s TheAustralianLegend review): Both feature pianists, which is not surprising given Richardson was a keen musician who studied […]

LikeLike