My late father had retired by the time I was doing my Masters so I kept him busy with a list of the books that I was having trouble finding and he would scour Melbourne’s second-hand bookshops. Consequently my Miles Franklin shelf includes half a dozen biographies and a whole string of Aust.Lit. overviews, from HM Green’s A History of Australian Literature to Clement Semmler ed., 20th Century Australian Literary Criticism.

My Miles Franklin biographies are:-

Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography (2008) which I got (new) for my birthday when it came out in the final years of my 7 year struggle to finish.

Marjorie Barnard, Miles Franklin (1967)

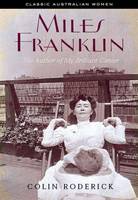

Colin Roderick, Miles Franklin: Her Brilliant Career (1982)

Verna Coleman, Miles Franklin in America: Her Unknown (Brilliant) Career (1981)

W. Blake, Miles Franklin: Novelist and Feminist (1991)

Sylvia Martin, Passionate Friends (2001)

Miles Franklin, Childhood at Brindabella: My First Ten Years (1963)

Not to mention her diaries and letters and importantly, all the essays introducing republications of her work, for instance Elizabeth Webby in My Brilliant Career/My Career Goes Bung, A&R (1990) and Roy Duncan in On Dearborn Street, UQP (1981).

Jill Roe’s is of course the most comprehensive, but the others have their uses and Verna Coleman’s is very good on MF’s time in Chicago. Sue (Whispering Gums) warned me off the Colin Roderick some time ago but I was reading it late at night, just to get it out of the way really, while some recent MF posts were fresh in my mind, and it was quickly obvious that she was right. Roderick’s disparagement of Franklin is so blatant, sexist and disagreeable that I thought I would write about it.

Colin Roderick (1911-2000) was an important figure in Australian literary circles and a vigorous promoter of Australian Literature. He was editor at Australia’s premier publishers, Angus & Robertson, 1945-65, and a director from 1961-65, foundation professor of English at James Cook University 1965-76, and was appointed to the inaugural judging panel of the Miles Franklin Award under the terms of MF’s will, which position he held until 1991, “when he resigned in acrimonious circumstances over the definition of what constituted a work of Australian fiction.” (Pierce)

In his obituary for Roderick (presumably in the Age of 16/6/00 – Dad has cut it out) Peter Pierce writes that “Roderick began a remarkable career as an author in 1945, with The Australian Novel. This was followed by critical and biographical works on Rosa Praed (1948), Miles Franklin (1982) and ‘Banjo’ Paterson (1993). The height of Roderick’s literary scholarship is represented by his impeccably edited, multi-volume collections of Henry Lawson’s verse and prose.”

I have Dad’s copy of The Australian Novel with his name and the year 1947 (it must have been set for Teachers’ College) inside along with the price (10/6) and the obit cutting. Miles Franklin has supplied a Foreword which includes:

… extracts from the literature of the British Isles and other parts of Europe, included in the class readers of my mother’s and grandmother’s times, were treasure trove to me before I was twelve. A little later came the discovery of Australian writers like Marcus Clarke, Rolf Boldrewood, Gordon and Kendall… Fuller enchantment came with Lawson, Paterson, and others not so prominent.”

So, no women writers for young Miles. In 1945 Roderick was a Gympie, Qld school teacher but he had an MA and this book was his path to a doctorate. In fact, only two pages of it are his and the remainder consists of 19 extracts from Australian novelists, 11 men and 8 women. Without payment. Roe writes, “when Roderick told Miles he was doing it for the good of Australian literature but expected to get a D.Litt. for his efforts, she set about organising a boycott.” This petered out and all the authors or their estates gave grudging permission – no doubt many of the anthologised novels were out of print.

Roderick was an early advocate for the Brent of Bin Bin books, and though of course she never acknowledged her authorship of them, Miles was inclined to cut him a little slack. In the small world of writers and publishers in Sydney they inevitably met quite often but never had a good relationship.

According to Roe, “whereas [Barnard’s biography] sought to elucidate the legend, Roderick tried to demolish it. (No doubt Roderick was shocked to discover from her papers [released 10 years after her death] what Miles really thought of him.)”

At the time of her death in 1954 Franklin was a writer of the Pioneer school, and decidedly out of fashion, but the rise of second-wave feminism in the late sixties, aided by the release of a film version of My Brilliant Career in 1979, made her anti-marriage heroines relevant again. Dozens of editions of My Brilliant Career were released around the world, My Career Goes Bung was reissued a number of times, and in 1986 even Some Everyday Folk and Dawn was ‘rescued from obscurity’ by Virago.

This seems to have made Roderick – who was after all a far north Queenslander – uncomfortable. He had Miles pigeon-holed as rural, out of date and eccentric and to apply to him the ‘psychology’ he is fond of applying to Miles, he was probably miffed to have lost his hold over her re-burgeoning reputation.

When it comes to the chronology of Franklin’s family and of her life as a writer, Roderick’s biography is detailed and interesting – Roe remarks that Roderick had first access to MF’s papers but fails to acknowledge them – but when it comes to analyses of Miles’ character and writing, Roderick uses pop psychology and perhaps his (unacknowledged) unhappiness at his portrayal in her letters to paint an unflattering and inaccurate picture. Some samples:

[her] unshakeable conviction of physical inferiority and lack of physical attraction… converted her into a skittish coquette stringing two or three men along simultaneously and a synthetic man-hater… It forced her to become a defensively bellicose propagandist for feminist causes. (p.14)

To be a proper woman she needed to submit to a man:

One of her American suitors might with a sure instinct express his intention of putting her across his knees. Had one of her Australian beaux done so in 1899 [the American would not have needed to, ie. she would already be married]. (p.72)

… she spent the best years of her life as a lackey to dominating women who were natural obsessed feminists. (p.75)

The blighting of Miles Franklin’s career was the result of indiscipline during her literary infancy … When she had put the finishing touches on the ebullient perturbations of her adolescence, they fell into the wrong hands. So did she. [This] was to lead her into a quagmire of irrelevant and wasteful New Woman militancy. (p.76)

And so it goes on. Roderick gives no credit at all to Franklin’s lifelong devotion to women’s and charitable causes, nor to her important contribution to women’s writing during the years of first wave feminism; and of course the one book he does credit as ‘literary’ is that homage to men’s endeavours, All That Swagger (1936).

The final lines of My Career Goes Bung are: “Was a woman’s refusal to capitulate unendurable to masculine egotism, or was it the symptom of something more fundamental?” It was certainly unendurable to Colin Roderick.

Colin Roderick, Miles Franklin: Her Brilliant Career, Rigby, 1982

Colin Roderick, The Australian Novel, Wm Brooks, Sydney, 1945

Sue at Whispering Gums: Who is Colin Roderick? (here)

Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear, what an insufferable, opinionated and arrogant man. “Putting her across his knees”. That makes me apoplectic! Thanks for doing the hard yards on this Bill. (And I love the stories of your father scouring the bookshops for you. He was a teacher?)

LikeLike

A teacher initially. He was very ambitious and rose through the ranks as an inspector and bureaucrat, but he mellowed after retirement and even read some Australian Lit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Retirement can mellow some people I think, Bill, particularly those who decide to enjoy it and who have (or find) some interests to follow. It’s nice to see.

LikeLike

You’re a very nice person, Sue. I mostly see the worst in people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, Roderick was a patronising pain… but even if he didn’t like her and didn’t think much of her writing, she trusted him to administer the MF award and he did try hard to defend it against its saboteurs,

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suppose he has his good points. The biog. ends “[Miles] herself applied the word ‘brilliant’ satirically to her writings; no one can apply it in that way to the award she created.”

LikeLike

Haha, she probably knew how conservative and sure of his own rightness he was – perfect for being a stickler for rules. (I was a bit harsh in my response up there – I know he did support Aus Lit and there’s an award in his name – but that attitude to women is insufferable!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yup, you’re not wrong!

LikeLike

I read this post while have a break from writing my book on Praed. Roderick put together the finding aid for Praed’s papers in the NLA and left offensive (by today’s standards) annotations throughout (although I am hugely grateful for the finding aid given the amount of material there is). His biography of Praed, ‘In Mortal Bondage’, was bizarre & bordering on fiction in places. I’m glad to see my suspicions of him confirmed – I thought I was just being a bit sensitive.

And by the way I am very much enjoying your blog & your considered attention to books.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To start at the end, thank you, we all love books, but I’m glad it shows.

I was interested when I saw that Roderick had written on Praed, no one, even at the time seemed to pay her much critical attention. I wondered idly if it was the N Qld connection. I’ve been a bit slack myself in following up the anti-marriage thread in C19th women’s writing and I’d better put Praed and Spence in particular on my reading list for 2017 (though just to be perverse, I think Tasma will be next).

LikeLike

Tasma is the other long-stander on my TBR, bought about the same time as Louise Mack! I’m planning to get to that book this year too.

LikeLike

You do Uncle Piper. I’ve been carrying it in my work bag in case of breakdowns, but I have a book of Tasma short stories and Clara Morrison to replace it.

I’ve read Uncle Piper, it’s a very Melbourne book, and a nice romance, from memory.

LikeLike

[…] Colin Roderick, Miles Franklin: Her Brilliant Career (1982), Review […]

LikeLike

[…] have reviewed two such biographies, Brian Mathews on Louisa Lawson and Colin Roderick on Miles Franklin. The former is a good example of a man being able to write sympathetically and insightfully about a […]

LikeLike

[…] Wilcannia was then and is now a very small desert town on the Darling in far western NSW so it’s unlikely the Western Grazier had a dedicated book reviewer. Further, some of the lines used in the article are those of the judges, so I’m guessing the story was provided by The Bulletin (though it sounds very Colin Roderick). […]

LikeLike

[…] appears in a less than glowing light – also wrote an MF biography, though as I’ve written elsewhere, not one worth […]

LikeLike

Yikes!

He sounds like an insufferable bore!

I’m glad you read this so the rest of us don’t have to.

I’m continually amazed by how our literary world is so interconnected. I probably shouldn’t be given how small it was/is, but it is fascinating to hear how they all rubbed up against it other, for good and bad.

LikeLike

Thanks for taking the trouble to find this Brona. Roderick was an important advocate for Australian writing, and was far better rewarded for it than Nettie Palmer, say (though Vance had some official positions), but he was also an insufferable dickhead. In the 1930s writers in NSW were pretty close, under the banner of the Fellowship of Australian Writers, and it is probably there that Roderick and Franklin met.

LikeLiked by 1 person