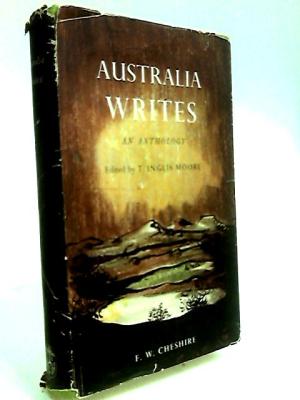

My late father’s books are an endless resource, more than I’ll ever read, not before I retire at least and by then I’ll be too tired. I’ve shelved them with mine, not so ordered as Lisa’s, so I come upon them at odd times. The bookcase on my left as I write – jarrah shelves roughly knocked together by an old family friend of Milly’s late mother, years ago when she was a widow with six school age children – contains mostly stuff from when I was studying, Miles Franklin, her contemporaries, Lit. theory, but I found` there today Australia Writes (1953), a compilation of short stories and poetry “written or published since 1950” and which Dad must have got second hand (for $6.00, compared with the original price of 19/6 – 19 shillings and 6d for all you youngsters, or just under $2.00).

The title page says “Edited for the Canberra Fellowship of Australian Writers by T. Inglis Moore”. Moore (bio here) writes in the Foreword –

Within its diversity the fiction … holds characteristics common to contemporary Australian writing. It turns frequently to the countryside – perhaps because writers feel that the true traditions of Australia lie in “The Bush”. It is marked by vigour and sincerity. The feeling for social justice is pervasive. The outlook is upon a workaday world; over it we could hang the roadside sign: “Men at Work”.

Men at work indeed, of the 30 short stories, six are by women – Flora Eldershaw, Dorothy Harrison, Ethel Anderson, Kylie Tennant, Elyne Mitchell, Henrietta Drake Brockman. I didn’t count the poets, but it’s more or less the same, Judith Wright, 5 or 6 other women and 30 men.

Eve Langley’s there:

A youth, kicking the self-starter of a

motor-bike sends

A vast vibration out to the sun, and it

returns his shadow in rain.

Out from the sun startles the line of

things, and the flying cars

Set their undertones in a dark and

silver note upon the line.

(This year before it ends)

Drake Brockman’s is a puff piece about Miles Franklin; and Tennant’s is a funny, queer, all right – strange story, a slice of many lives during a flood in Narbethong (not the Narbethong NE of Melbourne I don’t think, but one on a river with a dam upstream).

The story I’ve chosen to review is The National Game by T.A.G. Hungerford, a West Australian writer about whom I wrote earlier this year (here). His ‘national game’ is not Australian football as I expected but a two-up game in the national capital.

WG do you recognise this landscape?

Eastside Camp squats on the top of a red gravel hill and droops in untidy folds of unpainted wooden buildings down the slope to where a road skirts the willow-lined river… Behind it is the sky, and in front of it the road and river, and the lush greenness of the lucerne flats. Dotted with red and white cows, they stretch almost unbroken to Duntroon and the aerodrome.

Map (here): The camp may have been near Mt Pleasant, in the centre of the map. Lake Burley Griffin was not filled for another decade. I can remember visiting Nana and Pop, Dad’s parents when the lake was just paddocks as Hungerford describes.

Two men, Ransome and Kernow, an Old Australian and a New Australian, a Pole, called a ‘Balt’ by the Aussies, are workers on a project, maybe Civic (Canberra Centre), which was completed in 1961. Hungerford imagines what it might be like to be in Kernow’s head, dealing with the vagaries of slang and the latent hostility of ‘Old’ Aussies, who complain about foreigners taking their jobs, despite, as Kernow points out, there being a chronic shortage of labour.

Ransome offers to take Kernow to play two-up:

“I’m going up the game – up to Ainslie.”

“Game?”

“Yeah, the game. Swy – two-up, you know, with the pennies? At Limestone Hostel. They run a big one there in the scrub, behind.”

They play, Kernow wins, wins big, and they are chased home by some sore losers. Hungerford’s point is not the outcome of the game but to discuss aspects of Australianness by shining a ‘New Australian’ light on it. Kernow offers Ransome half his winnings, but Ransome demurs: “No Paul … we don’t do things like that here – you won it and it’s yours. Whack it in the kick.”

Kernow (note that Hungerford makes no attempt to give him a typical Polish name. Too hard.) is unhappy that he is not accepted by Old Australians even after two or three years and proposes using the money to return to Germany (Not to communist Poland!) but Ransome persuades him he has enough with his savings to buy some land.

To buy some land! His hands clenched hard about the the wads of notes they held; not the rich black soil of Poland, farmed and loved for hundreds of years by his father and his father’s father, but the wild soil of this wild, wide country that would have to be tamed, and coerced, and then, with love, brought to yield.

It’s an interesting book of our white picket fence past, those last few years before the ‘sixties’, womens lib, the anti-war movement, multiculturalism. Aborigines are, and would remain invisible for many more years. They get one poem, Nomads by Roland Robinson, and maybe a second, The Ancestors by Judith Wright of which I could make not head nor tail: “in each notched trunk shaggy as an ape/crouches the ancestor, the dark bent foetus …”

I should give it to B2, to mark his birth year.

T Inglis Moore (ed.), Australia Writes, FW Cheshire, Melbourne, 1953

Ah, these old treasures… they present a dilemma, to keep or not to keep, and if not, to whom should they be given so that they are not tossed out with the rubbish?

This week I received a copy of The Australian Author, 1969-2018 and I’m dipping in an out of it while the computer boots up in the morning. At the moment I’m reading Barbara Jefferis from 1969 on the subject of ‘The People Novels Write’ or the ‘Homo fictus’ who is created by the novel. After that there’s Judith Wright in 1976 on ‘Women Writers in Society’, writing about Eve Langley and Elizabeth Harrower when they weren’t treasures from the last century…

Would you like me to send this on to you when I finish it?

LikeLike

No problem for me, I keep everything. Would love Judith Wright on Eve Langley especially,

thanks.

LikeLike

No, I don’t recognise it Bill, and nor does Mr Gums who came to Canberra as a baby in the early 50s. My first visit here was about 1967, but I didn’t move here to live until 1975. Mr Gums was surprised when I asked him because he’d just heard a reference to Eastside Camp recently. His only thought was that it could be what he knew as Riverside Huts. They weren’t that far from your suggestion (but on the other side of the river – as it was then.) They were destroyed to make way for the National Gallery of Australia precinct. There was a bit of a hill there with slopes he said, but they were known as the Riverside Huts so? Duntroon would have been visible from these huts but across the river, such as it was.

LikeLike

Thank Mr Gums for his interest, maybe more clues will emerge. I was only guessing, and placed ‘Eastside’ on that side of the river to make less of a walk to Ainslie. We really have very little fiction about that first influx of migrant workers, and there must have been lots between Canberra and the Snowy scheme.

LikeLike

[…] NT Alexis Wright, Tracker (here) Tas Krissy Kneen, Wintering (here) SA Vic Peggy Frew, Islands (here) Free Claire Coleman, The Old Lie (here) WA Alice Nannup, When the Pelican Laughed (here) Qld Anne Gambling, The Drover’s De Facto (here) NSW David Ireland, The Unknown Industrial Prisoner (here) ACT TAG Hungerford, The National Game (short story here) […]

LikeLike