George Sand (1804-1876) was an influential (female) French writer and feminist, though I have no idea whether she was widely read in English before the C20th (Wiki says The Devil’s Pool was first translated in 1847). I wrote about Sand previously as the subject of Elizabeth Berg’s fictionalized ‘autobiography’, The Dream Lover, and have long had the intention of reading some of her work.

Sand grew up on, and became the owner of, her grandmother’s estate at Nohant in central France (Wiki). Since 1952 the house and gardens have been a museum. The Devil’s Pool (1846) was written relatively late in Sand’s career and refers back to the time of her childhood on the estate, a time which she regards as before modernization, particularly of course before rail made cross-country travel accessible to rural communities.

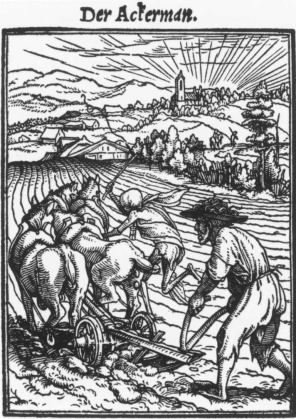

The novel begins with a contemplation of Holbien’s picture (above) of the devil driving a team of plough-horses, from his series ‘The Dance of Death’.

Shall we look to find the reward of the human beings of to-day in the contemplation of death, and shall we invoke it as the penalty of unrighteousness and the compensation of suffering?

No, henceforth, our business is not with death, but with life. We believe no longer in the nothingness of the grave, nor in safety bought with the price of a forced renunciation; life must be enjoyed in order to be fruitful.

We shall not refuse to artists the right to probe the wounds of society and lay them bare to our eyes; but is the only function of art still to threaten and appall?

We believe that the mission of art is a mission of sentiment and love, that the novel of to-day should take the place of the parable and the fable of early times, and that the artist has a larger and more poetic task than that of suggesting certain prudential and conciliatory measures for the purpose of diminishing the fright caused by his pictures. (The Author to the Reader)

So the story begins:

I had just been looking long and sadly at Holbein’s ploughman, and was walking through the fields, musing on rustic life and the destiny of the husbandman ..

At the other end of the field a fine-looking youth was driving a magnificent team of four pairs of young oxen ..

A child of six or seven years old, lovely as an angel, wearing round his shoulders, over his blouse, a sheepskin that made him look like a little Saint John the Baptist out of a Renaissance picture, was running along in the furrow beside the plough, pricking the flanks of the oxen with a long, light goad but slightly sharpened. The spirited animals quivered under the child’s light touch

These are Germain and his son Petit-Pierre.

So it was that I had before my eyes a picture the reverse of that of Holbein, although the scene was similar. Instead of a wretched old man, a young and active one; instead of a team of weary and emaciated horses, four yoke of robust and fiery oxen; instead of death, a beautiful child; instead of despair and destruction, energy and the possibility of happiness.

On the Librivox recording I heard the author say that she was surprised her work was regarded as ‘revolutionary’ but I can’t find the quote. I think the ‘revolution’ is that she has taken the old genre of Pastoral Romance with its lords and ladies and fairies and replaced them with ordinary peasant folk, and in doing so has written one of the prettiest little love stories I have ever read.

Germain, who is 28, has been some years a widower with 3 children. He lives and works on his father-in-law’s farm, and is I think effectively a partner in the business, along with his late wife’s brother. His father and mother in law have decided that he needs to re-marry, his sister in law is pregnant and they need another woman in the house to manage Germain’s children.

There is an amusing discussion on Germain’s great age and how he needs a sensible and mature wife and not one of the flighty young girls from the village. Father in law has in mind the widowed, childless daughter of a friend, who has a few acres of her own and who lives in a remote village beyond the woods, some ten miles distant. The journey is planned for the following Saturday and Sunday, and a poor widowed neighbour asks Germain to take with him her 16 year old daughter, Marie, who is going to a nearby farm as a shepherdess. On the day, Petit-Pierre inveigles his way into going with them.

I won’t tell you the story of their little trip, and their problems getting through the forest of the Devil’s Pool, but if you can, download the Librivox version, it is an absolute delight listening to Marie talk. She is one of those young women born full of common sense who have so often had to rescue me from my congenital idiocy, and I am more than a little in love with her.

Germain’s ‘intended’ turns out to be a flibbertigibbet and Marie’s employer a lecher and so they return home. All else turns out as you might expect.

George Sand, The Devil’s Pool, first pub. 1846 as La Mare au Diable. Gutenberg English translation here. I listened to a Librivox recording.

Lisa Hill of ANZLitLovers has a collaborative blog for George Sand (here) to which this post has been added. Lisa has my father’s copy of La Mare au Diable (I don’t read French) and reviews it over the course of three or four posts, starting (here).

[…] First posted at The Australian Legend (here) […]

LikeLike

Well done, Bill, I am so pleased that you are adding to the Sands blog, it’s a bit neglected but I am to remedy that in due course:)

LikeLike

We seem to have covered The Devil’s Pool in some detail. Time we looked at an earlier novel perhaps.

LikeLike

I read a great biography of George Sand back in my 20s but I’ve never actually read one of her works.

BTW I “won” an early reviewers copy of an historical novel about her through Library Thing a few years ago. I could not review it. It read like a history, not a novel, and then there was the writing! Here is an example of a sentence, just picked at random today when I opened the book (way past where I read to when I gave up):

‘In a period when Marie-Aurore was clearly near death, and yet had regained some of her mental faculties, so that she could communicate with those around her, Archbishop of Arles, or M. Leblanc de Beaulieu, the “bastard uncle” as Marie-Aurore called him, as he was the result of a publicized love affair between Marie-Aurore’s husband, M. Francueil, and the famous Mme. Louise Florence D’Epinay, who also had an affair with Rousseau, in 1756, even buying a cottage, before the two became bitter enemies.”

Life is way too short, I decided, to read a novel with sentences like this! If you can call it a sentence at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think a writer that bad should be allowed to escape without a review! Anyway I recommend the Berg, it’s very readable. And I recommend this story, even though it is tedious to download from Librivox, it is worth the effort. I listened to it for the second time driving around Melbourne rather than attempting to find a radio station (I know the frequencies of RN and 3LO, but I can never remember RRR.)

LikeLike

Fair point, Bill, but to have done that I could have had to read the book, but I gave up at p. 35. I just couldn’t do it.

The biography I read way back when was by someone called Noel B Gerson. I have no idea what I would think of it now as biographical writing but back then I enjoyed learning about the person he called “the first modern, liberated woman”.

LikeLike

Sand is certainly a contender for ‘first, modern, liberated woman’ but the more I go back the more my assumptions about women are tested. I think we are learning that it would be a mistake – a common mistake – to treat Sand as an isolated case.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My belief exactly!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A historical novel? That sounds odd. Were they trying to fictionalize Sands’s life and it came off poorly?

LikeLike

Read the Berg. It’s well done. Though of course I have no way of knowing if she takes liberties.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that’s what they were doing, Melanie. American writer. (PS I’m Sue! It’s hard keeping us all organised I know.)

LikeLike

Sorry, Sue! I knew that, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] (1864) is the 44th of Sand’s 60 odd novels/novellas. I have previously reviewed Sand’s The Devil’s Pool and Elizabeth Berg’s fictionalized and very readable bio, The Dream Lover, if you want more […]

LikeLike