Australian Women Writers, Gen 1 (1788-1890)

When Uncle Piper came out, in 1888 it was very well received and writers of the time likened Tasma to George Eliot (1819-1880). My own impression was to note the similarities with Elizabeth Gaskell (1810-1865), maybe because I have read her more, and more recently (here).

The similarities are in the frequent references to church and religion, a questioning tone, though Tasma seems more Agnostic than Dissenter, the predominance of female over male interests, and a general overall seriousness. Some critics mention Jane Austen, but Tasma does not have the great JA’s lightness of touch, or whimsy.

The novel is set in Melbourne, fictional Piper’s Hill is in South Yarra, a wealthy Melbourne inner eastern suburb; a ship approaching Melbourne; and in ‘Barnesbury’, Malmsbury, a minor gold mining town on the highway (and railway) from Melbourne to Bendigo. The period is the 1870s when Melbourne was the richest city in the world, following the gold rushes of the 1850s, and before the land boom and recession of the 1890s. The author mentions in passing Europe preparing for war. It is likely Tasma was in Belgium with her mother during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), so maybe she is referring to this or more generally to German expansionism.

Uncle Piper, now in his sixties, had come out from England as a young man, prospered as a butcher and then as a land speculator, and built himself a mansion in extensive gardens, with a tower from which he is able to see across the intervening suburbs of St Kilda and South Melbourne to discern with his telescope ships coming down the Bay from the Heads (map – Piper’s Hill is between Melbourne and St Kilda, beneath the ‘o’ say).

Piper has a son, George by his first marriage, and step daughter, Laura and much younger daughter, Louey by his second. Laura and Louey also have an older brother, a curate in London. Louey’s mother died in childbirth but Piper has promised to raise Laura as his own. Laura in young womanhood, accepts her step father’s support but not his rules and they are at daggers drawn, so when Piper realises George and Laura are in love he is seriously angry.

The cast is extensive and it is difficult to say if any one person is the protagonist, or even if we get to know any of the characters particularly well, though I like Laura, and it is likely she is the character Tasma has drawn to be most like herself. She and George are free thinkers. She is intensely loyal to George. She infuriates her step father by being beautiful, colourfully dressed, and by showing him the most studied indifference (Daughters! Who’d have them!). Laura and George also believe, theoretically anyway, in Free Love, which they discuss at length when Laura refuses to marry George on the grounds that he is not competent to support her if he is disinherited.

Piper’s sister was left behind in England where she married, above her station, Cavendish, an impoverished aristocrat. They have two daughters, the good, handsome Margaret and the thoughtless, impossibly beautiful Sara. They have lived poorly for many years on gifts to Mrs Cavendish from her brother, and at the beginning of the novel are at sea, outside the Heads, emigrants to Australia where Piper can more easily support them. Also on the ship is a curate, the Rev Mr Lydiat, who is of course Laura’s brother, coming out to minister to the colonies after wearing himself out in the slums of London.

The Cavendishes move into their own wing of the Piper mansion and the girls and their mother are introduced to a life of wealth and ease. Margaret though is insistent on supporting herself, and becomes Louey’s governess; Mrs Cavendish is induced to take over the reins of an extensive household; Sara – who has already rejected Mr Lydiat – keeps one eye on George, despite his humble birth, and another on the main chance, a title, a return in triumph to Europe; while Mr Cavendish chafes at being supported by ‘a plebian’, talks vaguely of a government job, and researches fanciful family trees. He is clearly a type Tasma has met and doesn’t like (Notice that she occasionally talks directly to the reader).

Mr Cavendish’s aristocratic nature was not devoid of the commonplace tendency I once heard attributed to husbands in general – [that wives are] to be petted and made much of when things are going well, and to be severely knocked about when anything goes wrong.

The plot is simple enough but what Tasma does, brilliantly and in detail, is describe the fluctuations in mood as the various young people form and reform alliances. Mr Lydiat still has hopes of Sara; George has all his hopes, for rescue from debt and marriage to Laura, riding on a horse he has running in the New Years Cup; Mr Piper has every intention of forcing George to marry Sara; Louey is distraught that her family is coming apart; Margaret is headed for spinsterhood while quietly pining after Mr Lydiat.

On the night before he is to take up a position in Barnesbury, Lydiat makes a fool of himself in the conservatory with Sara. Laura decides to go with him to give George and Sara space. There is a day in the sun at the races …

I won’t give too much away, but Louey takes the train to Barnesbury to be with her brother and sister; there’s an accident; all the family except Sara and her father rush to Barnesbury where they are all crowded into one little cottage. There are happy endings during which Tasma very much enjoys herself giving Sara her comeuppance.

My Thomas Nelson edition has as its front cover a Charles Troedel print of Melbourne in the 1860s. I couldn’t locate a copy so have put up this one of Eastern Hill which includes St Peters, the highest of high Anglican churches, where Mr Piper maintained a pew “and slumbered therein every successive Sunday.”

And I’ll reinclude a picture from my last post just so I can add Tasma’s description

Hotel Carlsruhe c. 1865. Now Lord Admiral House. “The great bluestone public house, designed for a monster hotel, was completed as far as its first story, but as it was never carried any farther, it naturally possesses at the present time a somewhat squat appearance, with a suggestively make-shift roof, and a general air of having been stopped in its growth.”

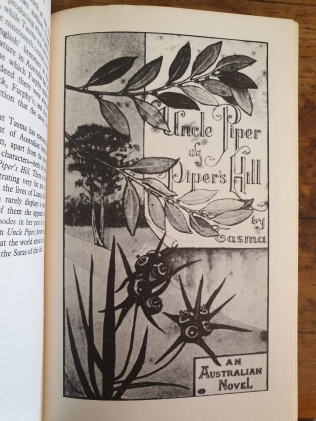

Tasma, Uncle Piper of Piper’s Hill, first pub. 1888. My ed. Thomas Nelson, Sydney, 1969. Top picture, reproduction of original frontispiece.

Download pdf version of first ed. (here) The Thos Nelson text is based on the 2nd ed.

Tasma (here)

Whispering Gums’ review (here)

Enjoyed reading this Bill. I enjoyed the book, and this brought it all back to me. I think I have her Sydney Sovereign in my TBR to read. One day!

Anyhow, I like your reference to Elizabeth Gaskell, though George Eliot is probably fair enough too. I’d have to read both of them again to think more about the similarities and differences with any depth though.

Thanks for the link.

LikeLike

Having a clergyman in the cast to facilitate discussions of religion and morality seems to have been quite common in the C19th. But of course it would take a whole other level of study to make a proper comparison.

LikeLike

Yes, and sometimes I think it would be fun to do that study wouldn’t it?

LikeLike

After reading your review, I went onto Goodreads to see what other said of this novel. It seems many people (include Sue! hi, Sue!) felt that the novel was wordy, some said the tenses randomly switched, and other problems with the writing. I’m always surprised that later editions of such novels are edited a little more neatly, not for longer sentences, as that was the writer’s choice, but for grammar errors.

They synopsis on Goodreads is confusing; it implies both that Piper lives in England and that he’s sending money to England. I’m assuming he’s in Australia but from England and sending money home to family, which apparently causes a ruckus.

LikeLike

Thanks for taking the trouble to look it up Melanie. It’s certainly wordy, as DH Lawrence or Nathaniel Hawthorne are wordy, it’s a novel about ideas and character, not about actions, and that’s what I like about it. And you’re right in your supposition, Mr Piper came out from England as a young man, made his fortune, and used some of it to help out his much loved sister who had made a not very good marriage, albeit one ‘above her station’.

LikeLike

Is it true that his family in England were miffed that he, the “lowly butcher,” was sending money home to them?

LikeLike

Mr Cavendish was embarrassed, not so much at receiving the money as at the possibility of his cronies finding out. Tasma makes fun of his (and Sara’s) pretensions throughout.

LikeLike

Hello Melanie – I did say it’s wordy! However, I’m not sure if you read on, but if you did you would have seen that I liked it, and that the wordiness was not something I saw as a flaw but as being of its time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I saw that and read your whole review. Wordiness isn’t necessarily a negative, depending on the book, and it can certainly reflect the time period. I’m reading David Copperfield by Charles Dickens right now, and it’s no wonder there’s a myth about Dickens being paid by the word!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Haha, great, Melanie. Just wanted to make sure!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It sounded good for me until the comments and “wordy” came many times and then the comparison with Hawthorne killed it all.

That’s not something I cound read in English and there’s no chance I’ll find a French translation. Too bad.

LikeLike

I understand, though I’m sorry I’m the one who talked you out of reading her. Perhaps I could point you instead towards Gen 3 in January – Kylie Tennant’s Ride on Stranger, maybe.

LikeLike

[…] Brief Take on the Australian Novel and his The Great Australian Novel, a Panorama. See also Bill’s review at The Australian Legend). But the Parisian romances, The Penance of Portia James and Not Counting the Cost, just […]

LikeLike

[…] authors Joseph Furphy and Tasma, and a little further on Malmsbury, the setting for Tasma’s Uncle Piper of Pipers Hill (1888). Closer to Bendigo, and off the highway a bit, are old gold mining towns Castlemaine (Mt […]

LikeLike

[…] women writers who preceded her, although by the 1890s Tasma for instance was very well known with Uncle Piper of Piper’s Hill (1889); Ada Cambridge was also writing in Melbourne; as were Catherine Martin and Mary Gaunt; Rosa […]

LikeLike