I should of course have written up my ‘namesake’ book years ago, though if you wished, if you had the fortitude, you might always have read my Masters dissertation, The Independent Woman in Australian Literature, which is one of the pages above.

This book attempts to trace the historical origins and development of the Australian legend or national mystique. It argues that a specifically Australian outlook grew up first and most clearly among the bush workers in the Australian pastoral industry, and that this group has had an influence, completely disproportionate to its numerical and economic strength, on the attitudes of the whole Australian community.

Ward, Foreword

The Australian Legend (1958) arose out of Ward’s PhD thesis, and it’s themes must have been ‘in the air’, as it followed Vance Palmer’s much less well argued The Legend of the Nineties (1954). It had an immediate impact, I think, crystallizing the thinking around Australia’s view of itself as a nation of knock-about, rugged, bush-savvy (white male) individualists despite the great majority of us (around 80%) living quiet suburban lives in the cities on the coastal fringes of our ’empty’ continent.

Feminist Gail Reekie wrote in 1992 that “Russell Ward’s Australian Legend has since its publication in 1958 constituted an almost irresistible magnetic pole of historical debate about the nature of Australia’s difference.” That is less true today, I think, as the multicultural (and multi-gendered) nature of modern society belatedly makes its way into our literature; but is still important, to decode the dog-whistling of right-wing politicians who use the themes of mateship, independence and (laughably) lack of respect for authority, to valorise military service; and to secure our placid acceptance of their post 9-11 incursions into our civil liberties.

I had intended this post as an ‘open letter’ to Marcie/Buried in Print, who is of course Canadian, to introduce her to Australia’s master of the short story, Henry Lawson. But that brought up so many other things – in my mind, anyway – that I decided to start from here.

Marcie, however, would recognise the foundations of the Australian Legend which begin with North America’s “Noble Frontiersmen” – fur traders, buffalo hunters, and then cowboys.

The wilderness masters the colonist. It finds him a European in dress, industries, tools, modes of travel, and thought. It takes him from the railroad car and puts him in the birch canoe. It strips off the garments of civilization and arrays him in the hunting shirt and the moccasin … he fits himself into the Indian clearings and follows the Indian trails. Little by little he transforms the wilderness …

FJ Turner, The Significance of the Frontier, 1893 (Ward, p.239)

In the C19th, in Australia as in America, the proportion of native-born was very much higher in the interior than on the eastern sea-board. Following Turner, the two most important effects of the frontier were to promote nationalism and to promote democracy. The US then was already a nation. I don’t know about Canada, but in Australia the outback (the “frontier”) was where the seeds of nationalism, independence from Britain, and the labour movement all took root.

Popular culture – from ES Ellis to Zane Grey to Hollywood – glorified the ‘wild west’, and while we outsiders always associated the US and cowboys, I imagine most Americans had a more nuanced self-image. The bulk of Ward’s thesis explores why in Australia this didn’t happen. Why we stayed fixated on the ‘frontiersman’.

He suggests that the difference is Australia’s aridity. In the US homesteaders headed out into the plains for their 160 acres of land, where their values were those of the small businessman. Australia however was taken up initially by squatters on runs of tens and hundreds of square miles, which only later were partially broken up so that settlers could take up square mile (640 acre) blocks. So by the recession of the 1890s there were great bands of itinerant workers roaming the interior seeking short term work – shearing, mustering etc, – and with a common ‘enemy’, the squatter, often an absentee living in luxury in Melbourne or London. Hence our real national anthem, Waltzing Matilda.

From the 1880s onwards, the Bulletin picked up on this, actively fostering nationalism, and providing a platform for descriptions of bush life. And so we get back to Henry Lawson, whose stories in the Bulletin provide much of the basis for the ‘Lone Hand’ myth or archetype; back also to my own thesis, and to Henry’s mother Louisa Lawson – born and married into poverty in the bush, single mother, raconteur, newspaper publisher, suffragist, Independent Woman.

I have written at some length in the past about both Louisa and Henry –

Brian Matthews’ biography, Louisa (here)

Louisa Lawson vs Kaye Schaffer (here)

My Henry Lawson by (his wife) Bertha Lawson (here)

Poetry Slam, Lawson v Paterson (here)

All My Love, Anne Brooksbank (here)

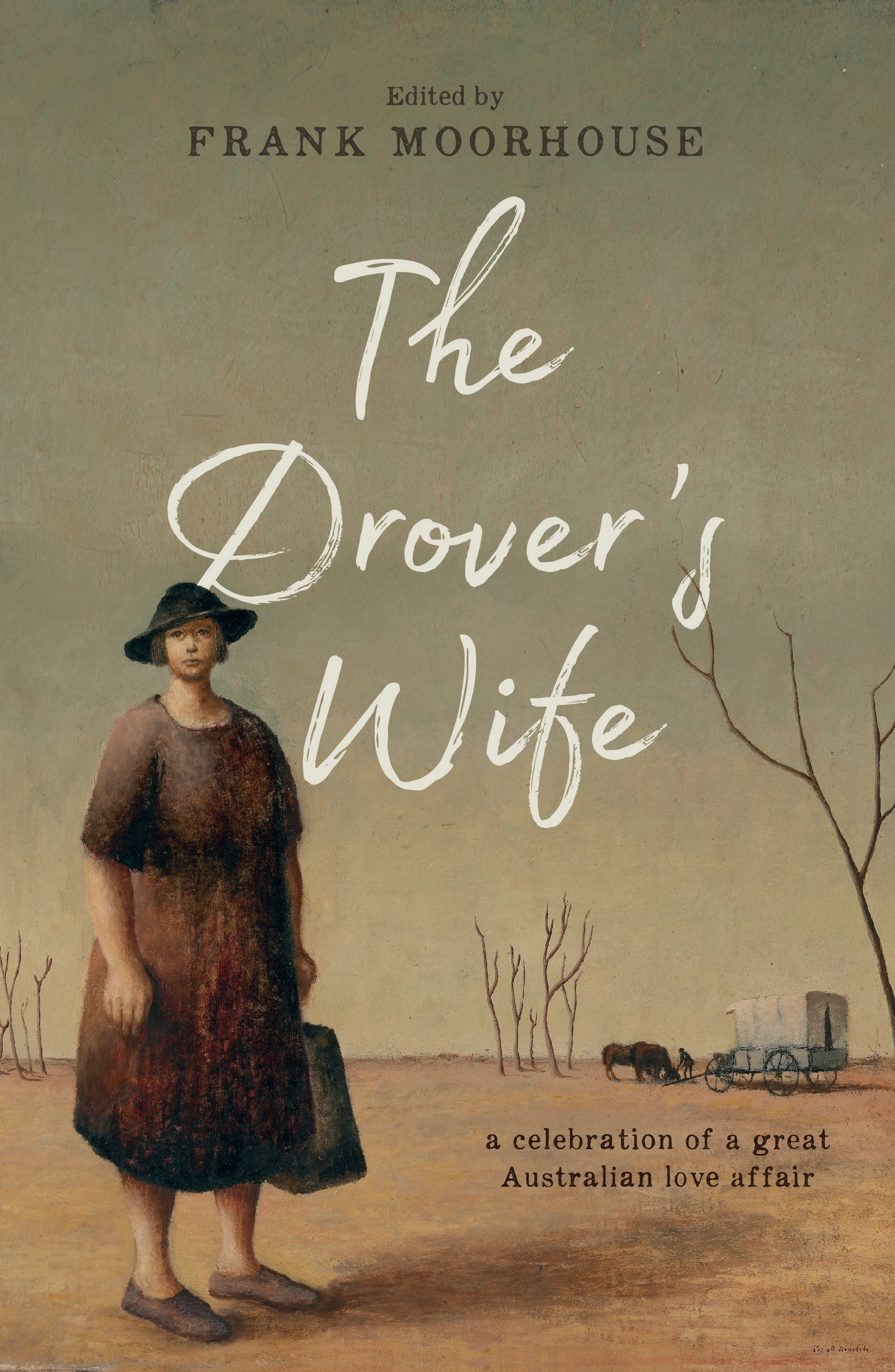

The Drover’s Wife, Frank Moorehouse ed. (here)

Henry Lawson (1867-1922) was born on the bush block in Grenfell, NSW where his father scratched out a living fossicking and droving, often away for long periods until Louisa got sick of it and moved to Sydney in the early 1880s. Henry’s education was greatly restricted by deafness, but he read widely. While working with his father as a labourer he had some poems published, notably A Song of the Republic in the Bulletin in 1887.

Meanwhile Louisa had purchased a small newspaper which in 1888 became Dawn, a newspaper for women, mixing housewifely tips with suffragism. In 1894 she published Henry’s Short Stories in Prose and Verse. I can’t see when his stories began appearing in the Bulletin, but in 1896 they brought out the collection which made his name, While the Billy Boils.

If you read Lawson closely, you can see Louisa almost as much as you can see Henry. So, The Drover’s Wife is a story Louisa recounted and embroidered on while Henry was growing up; in the Joe Wilson stories leading up to Water them Geraniums Henry redraws a young Louisa and Peter falling in love and then falling apart. Louisa has made Henry aware, in a way that adopters of the myth of the Lone Hand generally are not, that the lifestyle of the itinerant bushman is based on the subjugation of women. Henry just doesn’t know what he can do about it.

Ward concludes that “admiration for the simple virtues of the barbarian or the frontiersman is a sentiment which arises naturally in highly complex, megalopolitan societies.” Maybe. In any case, the Bulletin took Lawson’s “mates”, made them archetypal at a time when Melbourne and Sydney were still very conscious of the ‘frontier’ just over the ranges; united them with the nationalism which led to Federation in 1901; and then had them caught up and incorporated into the new myth of the brave, ruffian ANZAC, created in 1915 and which has proved ‘the last refuge of scoundrels’ ever since.

.

Russel Ward, The Australian Legend, first pub. 1958. OUP, Melbourne, 1981. 280pp.