I mentioned recently that I had seen Jonathan Franzen named as the Great American Author, on a 2011 Time cover I think, and that has led me to revisit the subject of the Great Australian Novel. There is a GAN was one of my earliest posts, and on re-reading I find there is not much I wish to change, at least not in what I say, but two books I have read since then (April 2015) cry out to be included. So my top 10 Great Australian Novels are now –

Voss (1957), Patrick White

Such is Life (1903), Joseph Furphy

The Swan Book (2013), Alexis Wright (review)

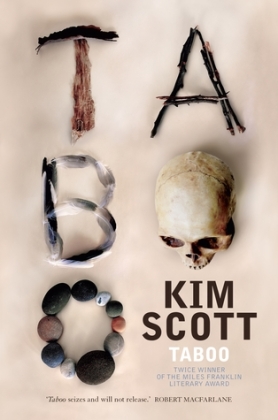

Benang (1999), Kim Scott (review)

The Pea Pickers (1943), Eve Langley (review)

The Man Who Loved Children (1940), Christina Stead

The Timeless Land (1941), Eleanor Dark

The Fortunes of Richard Mahoney (1930), Henry Handel Richardson

The Unknown Industrial Prisoner (1971), David Ireland (review)

An Australian Girl (1890), Catherine Martin (review)

The books I had to make room for were The Swan Book and Benang. Everything Alexis Wright writes is soaringly original, invested with poetry, love of language and Indigenous culture. That is true too of Benang though some of Scott’s other works are more prosaic.

And I’ve included too Eve Langley who in 2015 languished in the long list, not so much for The Pea Pickers, which I love, but for her whole body of work, 4,200 pages, largely unpublished, but samples of which Lucy Frost (ed.) used to produce Wilde Eve.

Dropped out were My Brilliant Career/My Career Goes Bung by Miles Franklin, who when young was an original, inventive, exuberant but still thoughtful writer; Loaded by Chris Tsialkos who I think is only a middle ranking author in middle age when I thought he might be much more; and The River Ophelia by Justine Ettler, a work which I still rank very highly but which perhaps is insufficiently mainstream to be one of the ‘greats’.

Voss clings to top spot. White, I get the feeling, is being treated as less and less relevant, but he was a giant of Modernism, in Australia and in the world. Each of his works on its own has substance and his body of work more so. He teaches us how to write and how to write about Australia. Coincidentally, the Voss cover comes from a SMH article Australia Day 2015: Jason Steger picks his top 10 (here).

Furphy is White’s opposite, a working man, a man of the bush, an autodidact, the author of a single work. And yet what a work! Its fiery, mad prose anticipates James Joyce by a quarter of a century.

Stead, like White has a significant body of substantial work. I’ve named The Man Who Loved Children, though my favourite is the thoroughly American Letty Fox: Her Luck (and I still have a couple of big ones left to read). Looking back at the list I see that I have largely avoided romances – just An Australian Girl at no. 10 – is that prejudice do you think? Perhaps I should have named For Love Alone.

That question applies too to Henry Handel Richardson. The Fortunes trilogy is certainly a fine work and made Richardson’s reputation but Maurice Guest is probably more thoughtful and better written.

The question for Dark is, Is The Timeless Land trilogy a great work or ‘merely’ an important one? It is such a landmark in our acknowledgement of the prior rights of Indigenous people in Australia that it is hard to judge its qualities as literature. But Dark’s qualities as a writer and early modernist were made apparent (to me) when I reviewed Waterway last year.

The Unknown Industrial Prisoner is another work important for being a landmark. Urban, industrial, postmodern, it marked a step up from pre-War social realism.

Which brings us to one of my favourites, An Australian Girl, a very C19th romance with lots of German and moral philosophy in an Australian setting.

And still I haven’t found room for Thea Astley or Elizabeth Jolley, or as Steger reminds me, Elizabeth Harrower, nor for Peter Carey whose Oscar and Lucinda at least, deserved consideration, nor for another Steger choice Marcus Clarke’s For the Term of his Natural Life.

I look around my shelves, as I often do, and realise that just as I left out Langley last time, this time I have left out (again!) Gerald Murnane. The post can stay as it is but if I were to pick one of his works it would be Border Districts, an intensely thoughtful work about memory, but again, I haven’t read them all.

The question I have in my mind though, is who among our young, and even not so young writers might challenge for inclusion on this list. Or a different/related question, after The Swan Book what is the best novel so far of the C21st? I’m inclined to say Heather Rose’s The Museum of Modern Love. Or is it, like The River Ophelia, too narrowly focussed to be a ‘great’. And do I even read enough new releases to be able to offer an opinion. Probably not!