Listening to this book over the last few days -relistening, I listened to it earlier but the intervening books just about wiped it out – I have been thinking about it as autobiography, struggling with whose story is it exactly.

The narrator of Nervous Conditions is Tambu, a girl from a small, traditional village in Rhodesia, in the 1960s and 70s, who goes to a mission school 20 miles away, whose headmaster is her uncle and the head of her family, and where she lives with her uncle and aunt and her cousin Nyasha, who is the same age as she, but a couple of years ahead in school.

Although we get close to Tambu, the really interesting character is Nyasha who, with her brother and parents, has lived in England for a number of years while her father (and later it turns out, her mother) have studied for masters degrees, presumably in Education. Nyasha has forgotten most of her first language, Shona, and has become a typical western teenager – more American than English as I remember those days, but that is just a quibble.

Reviewing Dangarembga’s later This Mournable Body, the third in her ‘Tambu’ trilogy, two or three years ago, I wrote: ‘The biggest difference between the author’s life and her protagonist’s is that Tambu’s parents are traditional people from a country village, while the author’s were both well educated school teachers’; and ‘It is possible that in Nyasha, the overseas educated cousin, with her degree in filmmaking from Hamburg, Dangarembga is having a little dig at herself “coming back to Zimbabwe where no one wants her”’.

Just a little bit of ‘research’ takes me to the position that Dangarembga did put most of herself in Nyasha and that Tambu is a – very well written – device for contrasting Nyasha with traditional life. From Wikipedia I get: “Tsitsi Dangarembga was born on 4 February 1959 in Mutoko, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), a small town where her parents taught at the nearby mission school. Her mother, Susan Dangarembga, was the first black woman in Southern Rhodesia to obtain a bachelor’s degree, and her father, Amon, would later become a school headmaster. From the ages of two to six, Dangarembga lived in England, while her parents pursued higher education.”

The central theme of the novel is how men are given all the advantages and how women are required to serve men’s interests. Maybe it’s just the books I choose, but those “intervening books” above were The Rise of Light by Olivia Hawker, set in a rural Mormon community in midwestern USA, and Rebel by Rahaf Mohmmed set in Saudi Arabia, in each of which a young woman must escape a domineering father whose authority is buttressed by traditional family structures; just as Tambu (quietly) and Nyasha (less quietly) rail against Shona custom which gives all privileges to men, and above all, to the senior brother, in this case Tambu’s uncle.

White settler colonialism plays a lesser part, but not no part. Tambu recalls her grandmother telling a story about ‘wizards’ forcing her well-off father off his land, and it quickly becomes clear these wielders of black magic are white settlers. There are remarks about the white missionaries – Americans, it turns out – dividing between those who send their children away to private schools with mostly white students, and those ‘going native’, speaking Shona and educating their children locally; but they, and later the Roman Catholic nuns are regarded as mostly benign. Bearing in mind that this is the period of Ian Smith’s illegal white minority government, Nyasha has learnt revolutionary opinions in England and occasionally expresses them.

But above all this is an ‘ordinary’ coming of age, of Tambu striving for the education that will enable her to break out of rural poverty, while her shiftless father and scheming older brother do their best to hold her back; and of Nyasha banging heads with a father high on his own self-importance, descending into depression and bulimia.

Tambu begins: “I was not sorry when my brother died. Nor am I apologising for my callousness, as you may define it, my lack of feeling.” And later in the first para. :”.. my story is not after all about death, but about my escape and Lucia’s; about my mother’s and Maiguru’s entrapment; and about Nyasha’s rebellion ..”

First, Tambo’s older brother, Nhamo, is able to stay on at primary school while she, due to her father’s mismanagement and poverty, must miss two years; then Nhamo sabotages her attempt to pay her own school fees by growing corn on some vacant land of her mother’s (and her grandmother before her); and finally he, given the opportunity to live with his uncle and attend the mission school, begins to hold himself aloof from his family; so that when he dies (of mumps) she ‘was not sorry’ and grabbed with both hands the opportunity to attend mission school herself.

Lucia is her mother’s sister. Tambu’s mother, first made pregnant at 15, is weighed down by children and farm work and Tambu’s father’s unwillingness to pull his own weight. Lucia, an outcast in her own village due to sleeping around, not getting pregnant and maybe being a witch, comes to live with her sister, continues sleeping around, but towards the end of the novel is able to break free, with a baby, but also with a job and the beginnings of an education. She is a background figure in the main story, Tambu and Nyasha’s story, but she obviously symbolizes something for the author.

Maiguru, Tambu’s aunt, must both teach and be a traditional wife when the uncle is being ‘headman’ as he often is. Only late in the novel does she assert her independence. Her principal role is to defuse the fights between Nyasha and her father and to maintain the father, her husband’s, self image as a righteous man.

After a couple of years at the mission school, Tambu wins a scholarship to attend a Catholic boarding school and she and Nyasha are separated. In this, Tambu follows her author, so perhaps Dangarembga has elements of herself in both girls.

As you might have gathered, this book is not ‘African’ in the sense that many others are with their all-pervasive spirits. But the descriptions of place and of culture are excellent. From that point of view the story could not be anywhere else; however in its themes of coming of age, and of coming of age as a young woman in a man’s world, it is universal.

The story is further anchored in Zimbabwe by the language, literary but straightforward, with just enough Shona, especially in the naming of relatives. Of course, I am held at one remove from the writing by the excellence of the reader and so I may impute to Dangarembga accents which are actually supplied by Chipo Chung, a Black Zimbabwean actress. Tambu tells us that conversations are occurring in a mix of Shona and English, but we are rarely aware of this from the writing itself.

Comings of age are my favourite form of novel. Nervous Conditions made me think a little bit about my own coming of age in the same years, and a lot about fathering, about banging heads with my own daughters, who mostly forgive me, thank goodness.

.

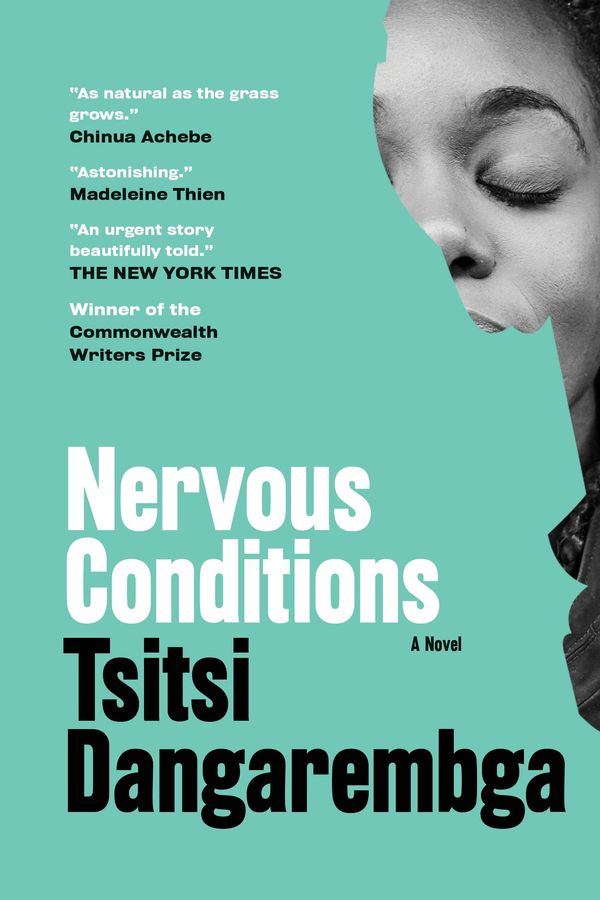

Tsitsi Dangarembga, Nervous Conditions, first pub. by The Women’s Press, London, 1988. Audible version read by Chipo Chung, 2021. 10 hrs

July’s Black African read will be Peace Adzo Medie’s His Only Wife (Ghana).

For Kate W.

The staple food of Tambu’s family is Sadza which is coarse maize (mealie) flour “cooked in boiling water or milk until it reaches a stiff or firm dough-like consistency.”

Here’s a recipe from ZimboKitchen. “Every household partakes of sadza nenyama nemuriwo (pap, meat and leafy vegetables) almost every day, be it supper or lunch. It is also one of the first foods that babies are given, usually at 6 months (some do it even earlier).”

One I’ve actually read – hooray – my review here https://librofulltime.wordpress.com/2022/10/03/book-review-tsitsi-dangarembga-nervous-conditions/. I haven’t read the other two in the trilogy as I liked this one so much I didn’t want to be disappointed. Very interesting info about which character she poured herself into – I don’t look up that stuff mysef being wedded to Reader Response Theory but it’s certainly interesting.

LikeLike

My worry is that if I do not know where the author is coming from then I am unable to extract any information from the story. If Nervous Conditions was written by say a Russian man then you could not have any reliance on it telling you anything about a) girls’ coming of age; or b) 1970s Zimbabwe. All you could say, as you can say of any fantasy, is that was an interesting, internally consistent story (or not).

LikeLike