One of the joys of watching Romper Stomper (Russell Crowe’s first movie), is the locations, around (Melbourne inner suburb) Footscray and particularly the freight rail line that crosses the Maribyrnong River and disappears under Bunbury St by the old Brown & Mitchell Transport depot to come out past Footscray station.

Footscray is a suburb of industry and workers cottages, of football team the doggies and of the big tech now Victoria University of Technology. Over the years I’ve delivered livestock from Newmarket to its various (long-gone) abattoirs, driven backwards and forwards through it when Footscray Road was Melbourne’s main transport hub, had jobs there, walked and eaten and banked there, way back then and more recently during all the years it was son Lou’s home base.

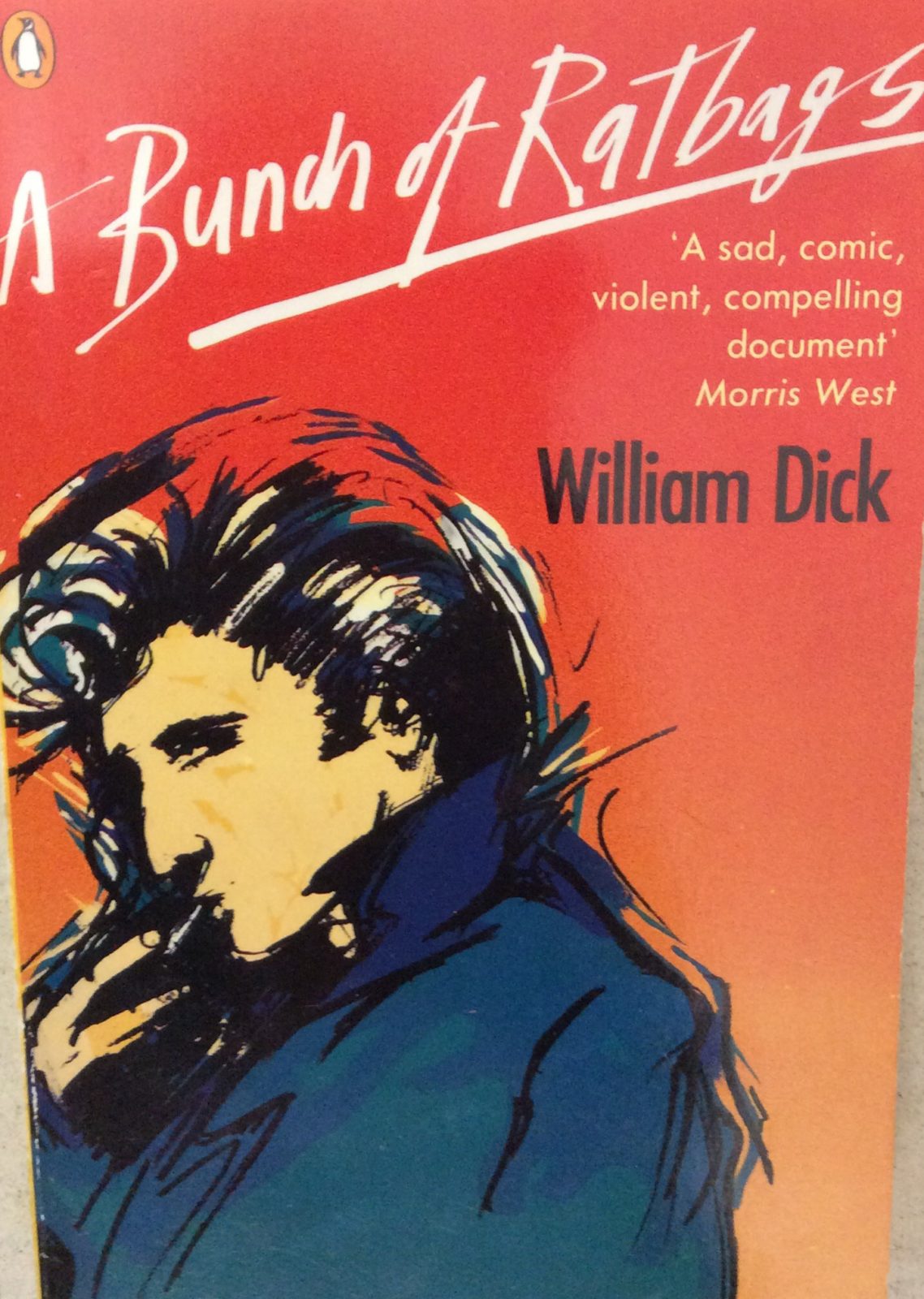

So I was looking forward to this 1965 novel of bodgies and widgies in Melbourne’s western suburbs, a working class bildungsroman, by an author for whom this was lived experience. William Dick (1937- ) grew up in Footscray in real poverty but worked his way out through a trade apprenticeship and a gradually developing career as a writer. By 1985 when this edition was published he had written two more novels and been to Stanford on a writing scholarship. I couldn’t find any more and a blogger I’ve linked to below who went to Footscray Tech in the 1960s concurs, but is able to identify many of the locations, including the protagonist’s (the author’s?) home.

By 1966 when our family moved (temporarily) to Melbourne, Bodgies (and Widgies, their female counterparts) had morphed into Rockers and the rival gangs were Sharpies, Mods and Stylists. Rockers followed Johnny O’Keefe, Mods Normie Rowe, and Stylists the Easybeats. Sharpies, I don’t know. They had short, short hair and wore wide tartan pants. They were rough. Working class kids who spent a fortune on clothes, on looking sharp, according to stories in the Sun. Dick spends a lot of time for a tough guy on descriptions of his clothes, and on the constant subtle changes of fashion. The Sharpies in his day, a decade earlier, were wannabe Bodgies but I think that by class and by attitude they ended up the real heirs of the Bodgies and the Rockers just got the hair and the music.

If an author says a book is a novel, then it’s a novel, and if it seems discontinuous then we look for connections. A Bunch of Ratbags reads as memoir, episodes in the life of, with the names, including the suburb, fictionalized to protect the innocent. The continuity is Terry Cooke growing from 8 to 18 and from petty thief to roughneck to good citizen.

And a warning: his attitude about violence to women is pretty blasé, though he redeems himself a little at the end, in his own eyes anyway, by stopping his mates gang raping a girl (though not till after they’ve bashed her).

The writing itself is disappointing, middlebrow, so that the slang when it’s used sounds false, almost parodic. The only similar book I know, Wild Cat Falling by Mudrooroo, sounds much more authentic. Dick writes like a journalist embedded in a gang, and feels the need to explain everything to us squares.

Cooke lives with his mother and father and younger sister in a falling down 3 BR single story weatherboard backing onto to the rail line. His father is variously a meat worker and an ironworker, doesn’t drink but gambles compulsively, a hoarder of things and animals – chooks, dogs, geese, lambs – a tyrant in his own little kngdom, a wife beater and a child beater. Cooke hates him and loves him.

– I just had to accept it, that my father liked to belt me up once in a while and that was that. After all, we were only normal people, and if every kid in Goodway murdered his old man after he got belted up, then there would have been no men left in Goodway at all.

As a youngster Terry has a range of little money making schemes, collecting bottles for refunds at the footy, salvaging woodscraps from the rail trucks carting firewood, selling newspapers, stealing.

When he starts at Footscray Goodway Tech he realises he’ll need to join a gang for protection and gradually becomes a little stand-over merchant in his own right. It is typical that when he discovers girls at 13 or 14 his first instinct (and his second and third) is to share, to take her into the toilets and to invite two or three of his mates to follow – he says he only does this with girls who want to “give it away”.

And so he makes his way through school, mostly in with the dumb kids, though sometimes showing enough promise to be put in with kids actually learning stuff; concentrating on his mates, fighting, edging his way into the local Bodgie gang based around the Oasis milk bar (just think Happy Days). At the end of four years, so aged about 16, he leaves, starts at the meatworks on good money but is made to realise that long term he’ll be better off with a trade and so is apprenticed to a furniture maker, alongside some big guys in the Bodgies.

From there it’s vandalism, sex, crime, drinking, gang fights, run-ins with police … and clothes –

The bodgie style had changed from jeans and so on to the new uniform of everything Junior Navy in colour – pants, shirts and socks. Cardigans were still the re-bob style. We now wore one-button, full-drape patch-pocket sports coats, but only the very light colours such as off-white, oatmeal, light blue or powder blue, with black shoes, suede or leather.

He graduates to captain of his own section of the gang. Bill Haley explodes onto the screen and then live at Festival Hall. He begins to get the shakes, headaches and diahorrea. Gets a steady girl who doesn’t do it. Seeks treatment. And slowly gets older and makes his way out of the system.

No, I didn’t like it particularly. Of course I loved that it was (more or less) my time, my home turf, but as a novel it was just a list of events, some of them unintentionally distasteful, with no tension, cardboard cutout supporting characters and very little character development even for Terry.

William Dick, A Bunch of Ratbags, first pub. 1965, Penguin 1984. Adapted as a stage musical (here)

Review by Footscray boy, blogger Rob Manderson (here)